Dementia is a growing health epidemic, but no one is paying attention

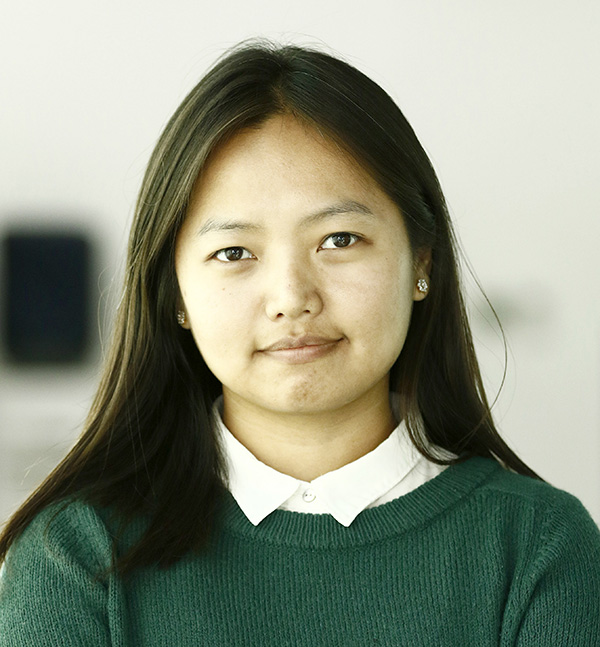

Pramila Bajracharya remembers when her grandmother started hallucinating. She would forget her way back home, accuse family members of not feeding her, and refuse to wear her clothes. The doctor told the family her nerves were damaged and there was nothing they could do, so they took her to a shaman, believing she could be cured. At the time, her family had no idea what her grandmother was suffering from.

She died seven years later, after first showing signs of Alzheimer’s disease, the most common type of dementia.

“We were desperate. We didn’t know what was going on with her,” said Bajracharya, who now runs a residential care home for dementia patients and has started an NGO, Hope Hermitage Nepal, to advocate for the rights of elderly people, particularly for those with dementia. “I wish I had known then that she was suffering from Alzheimer’s, we would have cared for her differently.”

More than 78,000 Nepalis suffer from dementia, a neurodegenerative disease which causes memory impairment, loss of cognitive and social skills, and eventually, the ability to live an independent life, according to the Alzheimer’s Disease International, a federation of Alzheimer’s associations around the world. Some estimates put that number even higher—one estimate, calculated using the five percent prevalence rate, says at least 135,000 Nepalis suffer from the disease. And the number is expected to double every 20 years.

But the majority of these cases, as with Bajracharya’s grandmother, remain undiagnosed. According to Alzheimer’s Disease International, 75 percent of people with dementia have not received a diagnosis, and therefore “do not have access to treatment, care and organised support that getting a formal diagnosis can provide.”

The percentage is believed to be much higher in Nepal, where a majority of the general population still does not understand the disease, and only a handful of hospitals is equipped to make a clinical diagnosis.

“People dismiss symptoms of Alzheimer’s as part of the normal aging process,” said Dr Nidesh Sapkota, head of the psychiatry department at the Dharan-based BP Koirala Health Institute of Sciences. “There’s still a lack of awareness about the disease in the country, both among the public and government officials.”

Because Alzheimer’s patients often suffer from behavioural abnormalities, which may include being physically and verbally aggressive, hoarding stuff, loss of bowel control, engaging in improper sexual behaviour, and wandering around without any sense of the place they’re in, they’re often confused to have a mental illness. This has led to the stigma surrounding the disease.

“As soon as an elderly person starts acting abnormally, society is quick to label them crazy,”

said Prabhat Kiran Pradhan of Alzheimer’s Related Dementia Society Nepal, one of the first organisations to actively work to generate awareness about the disease and lobby the government for policies to address it. “Most families often resort to isolating a patient in a locked room because they don’t know how to care for the patient.”

Caregivers struggle to put clothes on Vidhya Laxmi Shrestha, 64, who has been living at a residential care home for the past year. Tsering D Gurung/TKP

As the number of Alzheimer’s patients increases, there is also a growing need for trained caregivers who can provide adequate care and respond to a patient’s needs accordingly.

“If you have no orientation of the disease and do not understand why the person is acting in a particular way, you tend to take things very personally,” said Bajracharya. “And often that may result in lashing out at the patient.”

According to Bajracharya, all caregivers—whether they are family members or hired help—must undergo training.

“You have to use different tactics, some elderly patients need attention, some need to be distracted, some just need company,” she said.

Bajracharya said she has trained over 120 caregivers so far, many of who are domestic workers.

“My priority is to ensure the elderly stay at their home and have a trained caregiver there who can help when the children are unavailable,” said Bajracharya.

While there is no known cure for Alzheimer’s, early diagnosis, supplemented with proper care and treatment, can help delay the progression of the disease, according to medical professionals. On average, people with Alzheimer’s live between four to eight years after first showing signs of the disease, according to the Alzheimer’s Society, a UK-based charity that funds research on dementia. But some patients have lived for up to 20 years.

Early signs of dementia include forgetfulness, losing track of time, and becoming lost in familiar places, according to the World Health Organisation. As the disease advances, patients become increasingly dependent on others, facing difficulty with communication, needing help with personal care, and experiencing behavioural changes including wandering, repeated questioning and becoming conspiratorial. In the final stage of dementia, a person becomes totally dependent, unable to even move and feed themselves.

For years, Gaya Prasad Pradhan and his family had no idea what was wrong with his sister, Vidhya Laxmi Shrestha, a former Post Office employee from Tansen who had begun behaving irrationally, often shouting into the night, throwing things around, and urinating everywhere.

It was only after a visit to a geriatrician in Kathmandu that they finally found out she had Alzheimer’s. After her condition began to deteriorate, they decided to put her in a residential care home.

“It became impossible for us to care for her,” Pradhan told the Post. “She had to be watched 24 hours and there was no one in the family who could do that.”

Unlike other diseases, the impact of Alzheimer’s is often felt more by the caregivers—who are most often family members, who have to watch a loved one’s condition deteriorate over time— than by the patients themselves, say health professionals.

“It can be physically, emotionally and financially exhausting,” said Bajracharya.

The most difficult part is knowing they will never be the same, said Rupa Joshi, whose mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at 60.

Sharada Sharma, 89, who is suffering from Parkinson’s and dementia, is immobile and lives with other patients at the same care facility. Tsering D Gurung/TKP

“It’s like you’re watching them slowly die,” she said. “On days when the person is lucid, you grow hopeful that they’re back and better, but that moment is short-lived.”

After she started showing behavioural problems, the family stopped taking her to social functions as they thought it would be embarrassing.

“In hindsight, we should not have done that,” said Joshi.

Since the job of a caregiver can be mentally and physically taxing, Joshi said, the responsibility should not be left upon one person.

“Even if you have a nurse or a caregiver, family members and relatives of those who are suffering from Alzheimer’s should make it a point to visit them, spend some time with time, act like nothing’s changed,” said Joshi.

In 2013, Sapkota, who has been running a memory clinic at the Dharan-based hospital, conducted a year-long study with his colleagues, monitoring the number of people visiting the hospital’s psychiatric clinic, and found that over 11 percent of them had dementia.

“It’s is a growing health epidemic,” said Sapkota.

As in other countries, Nepal’s ageing population has been growing with the increase in life expectancy. Between 2001 and 2011, the total population aged 60 and above grew from 1.7 million to 2.2 million. As such, it won’t be long before dementia will soon be a major health crisis, affecting hundreds of thousands of families, health professionals say.

“The situation is dire but the government doesn’t seem to care,” said Pradhan of Alzheimer’s Related Dementia Society Nepal. “The state has no plans or policies to tackle Alzheimer’s which will continue to affect a growing number of Nepalis.”

In 2013, the government introduced the only significant provision that it has put in place to support Alzheimer’s patients so far—it will cover treatment up to Rs 100,000. But because the process is so cumbersome, not many have benefited from it.

To take advantage of the program, a person needs to first obtain a recommendation letter from their respective ward office and then get a clinical diagnosis from one of the 13 hospitals recommended by the Ministry of Health. Since these hospitals are exclusively in the cities, with nearly half of them based in Kathmandu, only a few people have taken advantage of governmental support.

Less than ten people utilised the service during the first three years of its provision. But in the last fiscal year, 69 people have taken advantage of the service.

“Think about those people who have to travel from remote areas to Kathmandu to first receive a diagnosis, and the amount they have to spend on transportation and lodging,” said Pradhan. “It’s just not convenient or feasible.”

And because the amount isn’t paid in a lump sum, they have to keep making repeated trips.

There’s also no state-run nursing home to take care of Alzheimer’s patients. Families have to rely on residential facilities run by private companies, which are expensive, ranging anywhere from Rs 30,000 to Rs 150,000 per month.

“The state needs to invest in the care of its senior citizens,” said Bajracharya. “There are many elderly people with the disease who are forced to live on the streets because they’ve been shunned by families. These people need a home.”