This ancient coin necklace is making a comeback

On a matunrolled comfortably in the garden, Himalaya, my aunt, pulls out a bag of old Nepali silver coins and spreads them out. One by one, she strings together the coins—each with a silver loop attached on the top—using a ball of green wool. She is making haari, a traditional jewellery made entirely out of coins, and popular among women in the Rai and Limbu communities. Next to my aunt, my grandmother, Kirti Sara, instructs her to weave tightly, keeping the spaces between two coins even.

When my grandmother was younger, growing up in Bhojpur, haari was the only piece of neck jewellery a woman could adorn herself with. As a young daughter of a British Gurkha veteran, my grandmother did not miss out, proudly flaunting two haaris.

“There was no limit to the number of haariyou could wear. The more you wore, the wealthier and more respected you were supposed to be,” she says.

I asked her why she doesn’t wear them anymore.

“Your grandfather sold it off to buy land,” she tells me.

There is no written history as to who wore haari, also commonly known as Company mala, in the beginning. Was it the Rais? Or the Limbus? Or was it the Sherpas?

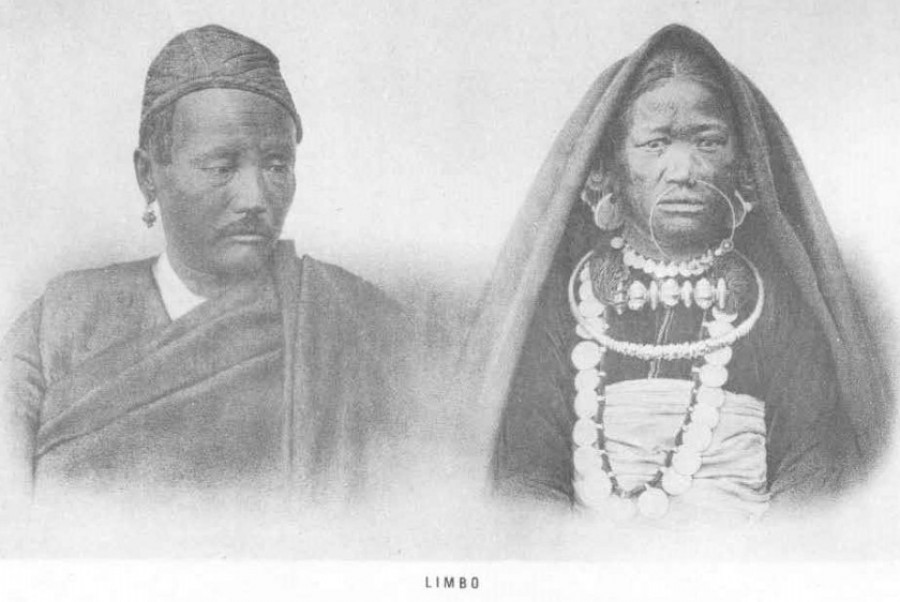

Dambar Chemjong, head of Tribhuvan University’s Anthropology Department emailed me a portrait of a ‘Limbo’ woman with a haaridangling down her neck. “It looks like she is from early 19th century Assam,” he said. The portrait was in a book by Edward T Dalton, an ethnologist.

The movement of people from eastern Nepal to North-East India in search of work and livelihoods dates back hundreds of years. This migration led to cultural exchange and influence, as can be seen in the Manipuri batuko, the singing bowl that was originally used to serve food in Manipur, according to Chemjong.

“North-East Indians, as well as Rais and Limbus who migrated there, could be seen wearing such pieces of jewellery, which is believed to have influenced Nepali women,” says Chemjong.

Many Nepali men, mostly from the eastern region, went to Darjeeling, Assam, Manipur, and Guwahati in India for trade, manual labour in the coal mines or as soldiers in the British, and later, the Indian Army. They would bring home their earnings in the form of coins minted by the East India Company—and later, the British Empire after the Indian Rebellion of 1857—which would be emblazoned with images of the King or Queen of Britain. These coins were turned into pieces of jewellery and worn by their wives and daughters.

Haariis inherently valuable, given that it is made up of currency. In those days, 25 paise could buy you many days’ worth of rations, so these long pieces of jewellery were signs of wealth, and therefore, a prime target for unscrupulous traders.

“Once a rumour spread that silver could not be worn as jewellery,” says my grandmother. “Everyone started selling off their jewellery to traders. We never learned who they were and where they took our jewellery.”

People also sold off their haaristo buy lands and properties.

Kirti Sara Rai, the author’s grandmother. Sikuma Rai/TKP

“My great grandmother owned a haari, but I heard from my father that she had sold it off to buy land in the village in the 1930s,” says Kajol Rai, a friend.

As these once-popular pieces of silver jewellery became a valuable object of trade, fewer women began to wear haarias jewellery. Slowly, its history and style was limited to the old black-and-white photographs of aging grandmothers.

On a recent Saturday, as I sat with my aunt and grandmother, I noticed that they were weaving the haari with old Nepali coins. My aunt then tells me of Sumnima Collection, where they sell a whole collection of haaris. So, I went to Talchikhel to meet Kapil Rai, the shop owner who can talk about the Rai culture for hours.

About two decades ago, Kapil and his wife Januka started selling traditional accessories like haari, at places where Sakela festivities, the marking of plantation and harvesting seasons, are celebrated. Like many new-generation Rais, the couple had only heard about haarifrom their grandparents, but they had never seen anyone wearing them.

“In search of an accessory that would not only benefit us economically but would also help to preserve our culture, we came across the Reji mala,” says Kapil, using the other local name for haari. “It was its uniqueness and history that prompted us to produce these commercially.”

But Kapil needed coins to make haariand his first stop was Pashupatinath Temple where they purchased 21 pieces of one rupee coins. Januka learned the technique of threading together the coins from a relative and made her first jewellery.

A haari mala woven by the author’s aunt. Sikuma Rai/TKP

The couple then ventured across the Valley to acquire as many coins as possible. They even sent requests looking for ancient coins. From temple priests to the Valley Newars, they offered good deals to whoever was willing to sell their precious collections of coins—as much as Rs50 for a one rupee coin. Once the coins started coming their way, in thousands, Januka gathered a couple of women, taught them how to weave, and paid them a thousand rupees for making one necklace.

In recent years, the demand for the necklace has soared. So far, the Rai couple has sold more than a thousand haari malas of one rupee, 50 paise and 25 paise coins bearing the portrait of King Birendra. More than 50 sets of haari made withcoins that bear the portrait of King Tribhuvan, which are now worth Rs25,000 each, have already been sold. Haaris made out of authentic British Indian coins cost even more, ranging from Rs80,000 to Rs100,000, at a rate of Rs1,000 per one rupee coin.

“We are happy we were able to dig out our once-buried heritage and give it the importance and respect it deserves,” says Kapil, who tells me diaspora across the world, from Qatar to Hong Kong, and from the UK to Korea inquire him about his haari.

These days, the demand is so high that some people have started to weave them with coins from the countries they migrated to. Manlachhi Rai, wife of a retired British Army soldier, made a haarifor her daughter-in-law using 10 pence British coins. Having seen many people do the same, she collected the coins during her stay in the UK, and turned them into a necklace when her youngest son got married.

Others are willing to go to any length to find the original necklaces. Poonam Subba, with help from her relatives who traversed through numerous eastern villages, was able to find one haarimade from 50 paise coins that date back to King George VI in the early 1940s. Some three decades ago, she sold off twenty grams of gold to purchase it.

“Even though I rarely wear it,” Subba says “it carries a piece of history and it is very hard to find an antique haari these days.”